Table of Contents

Types of Decoders

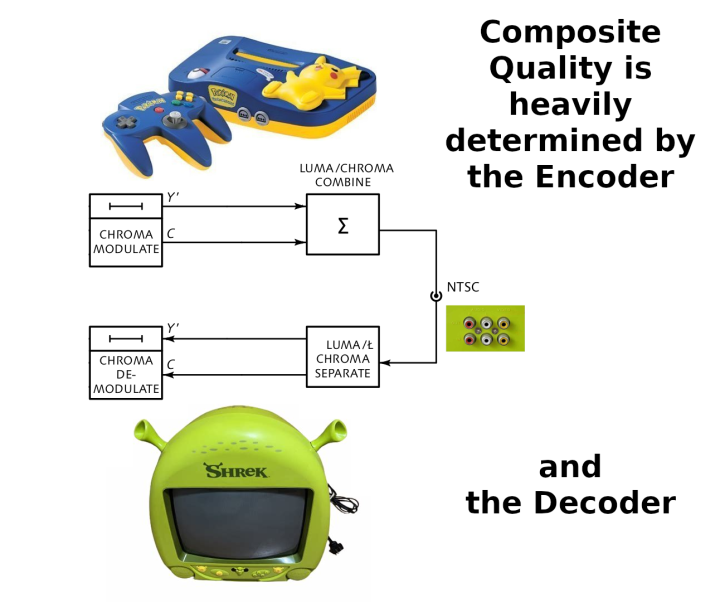

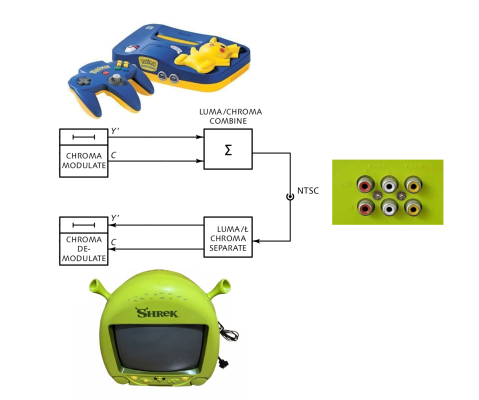

Composite video is so termed because luma (brightness information, Y) and chroma (color information, C) are combined, or composited, into one signal. In order for both aspects of picture information to be displayed by a color CRT, it must be decoded and have the Y and C separated from each other again. A display may handle this composited signal in three ways: 1. no color decoding 2. a notch filter or 3. a comb filter. Note that most comb filters are adaptive, which means they also use a notch filter for portions of the decoding process depending on the properties of the signal.

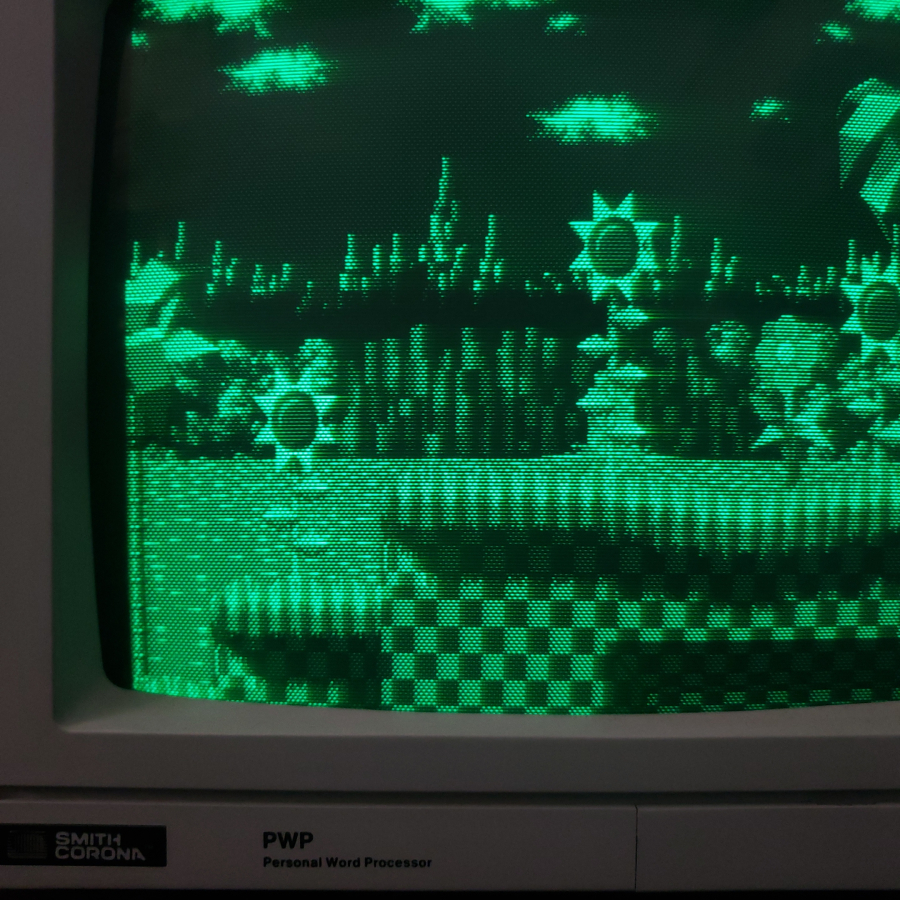

A display may simply not do any decoding, such as is the case with many monochrome sets and monitors. The result is that when color information is included in the signal, it can present as significant artifacting across the screen in the form of "chroma dots", since the color subcarrier is in no way excluded from the brightness information.

Atari 800XL computers had different video cables for monochrome displays versus color displays (the SECAM version used a switch on the back to choose between color and monochrome video output in lieu of different cables). Because of this, one could get better monochrome picture quality with no possibility of chroma dots. The Atari 800's color video signal is called "composite video", and the video signal for monochrome monitors is called "composite luminance". The latter is like the Y signal (green cable) of component YPbPr, which likewise does not cause the same issues when used with monochrome monitors that standard composite video does, with its extraneous and interfering color information.

"[Composite] interleaving works well for static and low saturation color picture information, so long as chrominance levels do not exceed 20%. When high chrominance energy levels are present, the dot pattern levels in the luminance path are excessive. It is therefore mandatory to filter out the subcarrier" -Method and Apparatus for Separation of Chrominance and Luminance, Faroudja, 1980

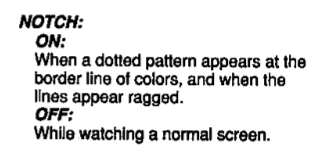

The first way to decode a composite signal is by way of a "notch" filter, and its implementation involves a combination of filters. The series resonant notch portion, also known as a chroma trap, bandstop, or bandreject filter, is intended to remove the color information in order to have just the brightness information (implementations may also use a lowpass filter to remove chroma instead). As for isolating the color information, a parallel resonant bandpass filter is used. Because the performance characteristics of the specific filters used vary, so too does the resultant picture quality vary as well - all notch filters not created equally.

The second way to decode composite is with a comb filter, which as previously noted, is commonly a combination of a comb and a fallback notch/bandpass. Instead of separating Y and C by means of passing and blocking whole regions of the signal, the comb attempts to separate Y and C information by means of de-interleaving. While being able to capture more high frequency detail than a notch filter, one of the areas where a comb can perform more poorly than a notch is across certain picture element transitions; adaptive comb filtering can detect this and divert processing to the notch instead, or even use an average of both the comb and the notch.

Combs are often categorized by how many scanlines they are comparing and averaging in the same field (2-line, 3-line), or termed "3D" for when they compare and average lines from neighboring fields over time (an additional, temporal dimension). In order to compare neighboring scanlines there must be a mechanism to delay a scanline. One method is a glass delay line that turns the scanline into an ultrasonic sound wave and then back into an electrical signal. Later comb filters converted the analog signal into digital form as a way to store it for comparison.

Are Comb Filters Better for 240p?

Since comb filters are advertised as a "step-up" feature, and they require more sophisticated circuitry than notch filters, they must produce a superior picture for home video game 240p content, right?

"Generally, for every gain in performance obtained in one area, there is a penalty to be paid in another. Luminance/chrominance comb filtering is not a panacea...It is always possible to configure a subject for televising that will be noticeably degraded by comb filtering." -SMPTE Journal Volume 86 Issue 1

"Proper operation of a comb filter depends upon the video signal having stable timebase and coherent subcarrier...If any of these conditions fails, as is likely with video originating from a consumer device, then comb filtering is likely to introduce artifacts and a notch filter should be used instead." -Digital Video and HDTV Algorithms and Interfaces, Poynton, 2003

"For retro-consoles such as the NES that use off-spec encoding and contain sharp edges, it is recommended that the switch be left in the ‘Retro’ position. This forces a notch based filter that minimizes ringing and other artifacts. The notch filter has lower horizontal resolution but is free from vertical comb filter distortions." -RetroTink 2X-Pro Manual

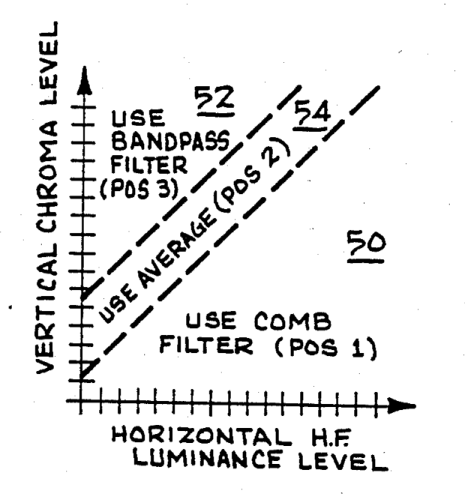

Note below how JVC instructs to switch from the comb filter to the notch filter when dot artifacts are visible:

Comb filters are not necessarily better for all composite content, particularly home video game 240p content. The quality of the composite picture is heavily dependent on the quality of the source encoding (the game console), and how it's handled by the decoder (the TV/monitor). What complicates this further is that performance can vary noticeably from one notch filter to the next, as well as from one comb filter to the next, even of the same type or manufacturer. For 240p, a good notch filter is better (has less artifacting) than most comb filters, though a particularly good comb filter can also be better than many notch filters.

In contrast to some other video standards, the properties of composite picture performance are much moreso a case-by-case scenario, demanding knowledge of the exact components involved for the resulting picture to be described with much accuracy. As such, generalizations regarding the picture quality of composite will very often entail oversimplification and hence be inaccurate & misleading. When it comes to composite, the devil is in the details.

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a